To celebrate International Women’s Day 2024 we shine a light on Ann Harriet Pottinger, née Hunter, one of many unsung, hard-working Shetland women who made a difference to their community and family.

In Ann’s case, she also contributed in a small way to world events. She was a businesswoman, mother of eleven, and wife of the schoolmaster in Brettabister, Nesting at the end of the 19th century and the beginning decades of the 20th century.

The family, 1906, top left: sister-in-law Liza Irvine, Bella, Liza, Ella, William Jnr., James, Frank, Harriet, William Snr., Maggie, Bob, Ann, baby Vera. Photo taken by Ann’s brother Robert Hunter.

Ann (1867-1929) was born at Quoys, Billister, North Nesting. Her father was a merchant seaman and she was the second eldest of five children. We do not know about her early life but she attended school as a child, possibly at Laxfirth, North Nesting. Her husband, William Pottinger (1855-1926), was 12 years her senior and a schoolteacher by age 25. They wed on 28 December 1888, she was 21 and he was 33 years old.

Brettabister schoolhouse and Pottinger family home. The church is in the middle distance, with Neap beyond.

For the first 18 years of her married life Ann was pregnant, giving birth to 11 children between 1889 and 1906. Her first four children were born at the Laxfirth school, and then in 1894 or 1895 the family moved to the schoolhouse at Brettabister, where the remaining seven children were born. Theirs was a busy house: it was the local schoolhouse, home to 13 people and by 1901 William was also a sub-postmaster, as well as teacher.

William and Ann survived two of their children. Ann’s daughter and namesake, Annie Harriet, died at ten months old. Three years after the death of their daughter, Ann gave birth to another daughter and named her after Annie Harriet, a common convention at the time. Their son Francis passed at age 18 in 1917 from meningitis. He had been a private in the Seaforth Highlanders, 3rd Battalion during the First World War.

The family at a large Nesting wedding, 26 December 1912. Ann is on the far left in fancy white hap. William stands further behind in bowler hat. Photo taken by Ann’s brother Robert Hunter.

By 1913, Ann was running a knitwear business. In this year Sir Ernest Shackleton was preparing for his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition and Ann’s business became one of the suppliers of knitted clothing. There was to be a total of 28 men divided into several parties, some crossing by land, others remaining on board the two ships, Endurance and Aurora. As we know, the expedition did not go according to plan and the men became stranded for over a year, returning toward the end of 1916.

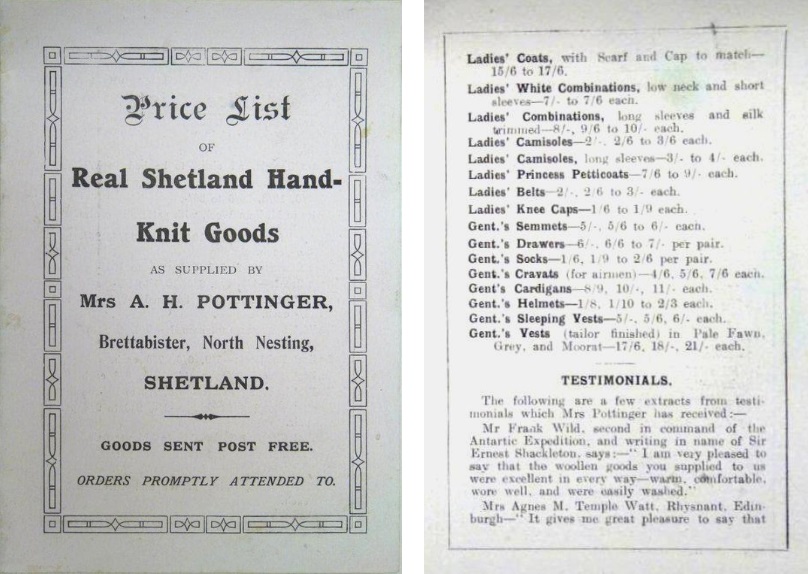

It is not clear what garments Ann’s business supplied, but the Shetland Archives holds several documents which give us a small insight into her contract with the expedition. She printed a price list (D6/294/1/p.69) probably dating to early 1918. In it she quotes a testimonial from Frank Wild, second in command to Shackleton. His words are taken from a letter Wild sent to Ann on 1 December 1916 (D1/259/2), in which he reports, “I am very pleased to be able to say that the woollen goods you supplied to us were excellent in every way, warm, comfortable, wore well and were easily washed”.

Wild’s description may be brief, but the qualities he describes were crucial to polar explorers. From Ann’s price list, we see she was able to supply Shetland woollen socks, long-sleeved undershirts (semmets), balaclavas, drawers and sleeping vests. There may have been more than one of each garment supplied to the men, since they expected to leave stores in the ships as they crossed Antarctica. Explorers at this time typically wore three or more pairs of socks at one time to avoid frostbitten feet. All of these garments were worn next to the skin to provide the best insulation. In the case of Wild’s crew, who were stranded on Elephant Island for a period of over sixteen months, it was vital their remaining gear lasted until they could be rescued. During their wait, clothing was only removed to be washed. This not only cleaned them but reinstated their thermal properties, since the Shetland wool would have regained its natural loft once dry. These are the qualities Wild was complementing in his letter to Ann.

Ann Pottinger’s price list hints at further business opportunities for her. She was able to supply Gent.’s Cravats and notes they were “for airmen”. She was referring to the Royal Flying Corps stationed at the Catfirth Air Station in South Nesting in the First World War. Up to 450 airmen were stationed here in early 1918. Their job was to fly seaplanes along the east coast of Shetland as far south as Fair Isle, to look for German submarines. Following the armistice, the base was closed in April 1919.

Seaplane damaged in a gale at Catfirth Air Station, 1918.

In 1922, Ann and several other Shetland women won a knitting contest sponsored by The British Cellulose and Chemical Mfg. Co. Ltd, to design a garment using a new type of yarn made from cellulose acetate, marketed as “Celanese”. The company needed fashionable designs to enable Celanese to be more widely manufactured. This date is at the cusp of the boom in fair isle knitting and Celanese and other ‘artificial silks’ were used extensively by Shetland knitters into the 1930s. As always, Ann was looking forward, to the future and new possibilities.